How to Teach Mindfulness to Kids

Episode 6 of the Secular Buddhism Podcast

Hello. You are listening to the Secular Buddhism podcast, and this is episode number six. I'm your host, Noah Rasheta, and today I'm talking about tips on how to teach mindfulness to children, or to your kids. So let's get started.

Welcome

Hey, welcome to the Secular Buddhism podcast. If this is your first time listening, thank you for joining. SecularBuddhism.com is my website and blog, and this podcast goes along with it. The Secular Buddhism podcast is produced every week and covers philosophical topics within Buddhism and secular humanism.

Episodes one through five serve as a basic introduction to Secular Buddhism and to general Buddhist concepts. So if you're new to the podcast, I highly recommend listening to the first five episodes in order. All episodes after that are meant to be individual topics that you can listen to in any order.

I like to start each podcast with a piece of advice from Tenzin Gyatso, the 14th Dalai Lama. He says, "Do not try to use what you learn from Buddhism to be a Buddhist. Use it to be a better whatever you already are." Please keep this in mind as you listen and learn about the topics and concepts discussed in this episode. And remember, if you enjoy the podcast, please feel free to share it, write a review, or give it a rating.

Let's Jump In

All right, well, let's jump into this week's topic. What I want to talk about today is mindfulness—specifically mindfulness for kids. I have a six-year-old, a three-year-old, and a four-month-old, and mindfulness has recently become kind of a routine at night with my kids. I wanted to share some of the tips and things that have worked for us as we've started talking about mindfulness.

And when I say mindfulness as a topic, I don't mean the word itself. My six-year-old doesn't know what the word "mindfulness" means. We don't actually talk about the word mindfulness, but we have specific routines and exercises that we've been doing that involve mindfulness. The ultimate goal is helping him become mindful without necessarily telling him, "Hey, this is what mindfulness is"—because young kids don't really get that.

A lot of this needs to be adapted based on the age of the children you're going to be teaching. But I think most of this stuff is relevant for kids of any age. Keep in mind that as I share this, my son is six and this was kind of tailored around him. My three-year-old is a little too young to really grasp any of this, but some of what we do also works with her.

How This Started

At night, we've developed these routines. Meditation is one of them. I was having this conversation with my brother on the phone last week, telling him a little bit about the things that we do, and he was very interested in taking notes and finding out what works for us to start teaching mindfulness to our kids. That made me think, "Maybe I should do a podcast episode and talk a little bit about tips and ways to teach mindfulness for kids."

So let me remind you: we've talked about mindfulness before. The whole purpose of being mindful is to train ourselves, to train the mind to become aware of things as they really are. Remember, our natural tendency is to take whatever is—the way life is—and then we add meaning and stories. We get lost in these stories and in the meaning that we create about things. What we're trying to do with mindfulness is just become aware of things as they are.

For kids, this can be pretty natural. But it's during the period of time that kids grow into adults that they really lose track of just allowing things to be what they are. Then they start assigning meaning, like we do as adults. So some of these exercises are just meant to increase that awareness and help them realize that the way they naturally do things is much more mindful than the way we as adults sometimes do things.

Four Main Exercises

There are four specific topics or exercises that I like to do. A lot of these are pretty new—I'm testing them now and seeing what works—and I'm sure this will evolve and change over time. But I wanted to share what's working for me and my kids.

1. Meditation: Starting with a Game

My six-year-old, Riko, is very into meditation right now. One of our routines at night started out almost like a game. He and his little sister Noelle, who's three, we sit down—they each have their own bed and share a room—and we'd sit down on the bed. Then it was like a contest: "Let's see who can sit still and quietly for 30 seconds." I would set the timer on my watch, and they would sit there.

Usually, she's the first one, at about the 15 to 20 second mark, who says, "Are we done? Are we done?" It's kind of become a little game to see who can last the longest. She's lasted all the way up to 60 seconds, which is pretty impressive in my eyes for a three-year-old. But she's consistently reaching 30 seconds now, and it's become a routine at night. She says, "Okay, let's meditate," and she'll sit down. She can last about 30 seconds, then she'll lay down and lay there quietly while her brother finishes his meditation. And nine out of ten times, she'll fall asleep while she's laying there waiting for him. So it's kind of become a win-win for the whole nightly routine of getting the kids to bed.

What's really impressed me with Riko, the six-year-old, is that starting at 60 seconds, this challenge became: "Oh, now can I do 100 seconds?" And then he did that. "Now can I do 200 seconds? Now can I do 300 seconds?" He's reached the point now where he can quite easily sit there for 10 minutes—600 seconds. What we do is he just sits there quietly, and I have my timer on my watch. When it hits 10 minutes, I tap him and say, "Good job, you did it." And he's just so excited because to him it's a challenge and he was able to do it. He loves knowing that it's not easy, and I always tell him, "Most adults can't sit down for 10 minutes." And he just loves knowing that he can.

So that's how he started to get into meditation. But really, we're just sitting there quietly. There's no specific thing that he's doing other than one simple rule: if you open your eyes, then you're done. I'll stop the timer. Or if you say anything—the moment you start talking, then it's over. I stop the timer and I'll tell him, "This was your score."

It's happened several times where he'll say something or open his eyes, and I'll say he's done. Then he'll say, "No, I wanna do it again," and I'll say, "No, that was your shot tonight. We can try it again tomorrow and see if you beat tonight's record." I think that's helped motivate his determination to do this well and stay sitting there quietly.

As he practices his skill of just sitting there and controlling his desire to talk or his desire to open his eyes, I think that's bringing about the awareness that I'm hoping he'll get out of it. There's a lot of control that can go into our habitual patterns. The habit might be "I wanna open my eyes," or the habit might be "I wanna start talking." To be able to sit there and evaluate that and say, "No, I'm not going to. I'm gonna sit here quietly until my dad says the time is up"—I think that's a tremendous sense of willpower that he's building up. That's going to be helpful in so many other aspects of his life.

Even my three-year-old, if she doesn't hit her 60 seconds, she kinda gets frustrated. She's like, "Ah, I wanna do it again." I usually let her try again because Riko's gonna be sitting there for a whole 10 minutes, so she'll try it until she can get her 60 seconds. Then she's really happy and proud of herself because she did 60 seconds. And then she lays down and goes right to sleep.

2. Teaching Impermanence: The Bell and the Clouds

There are a few other exercises that I've started to incorporate that I've found to be very successful in helping to accomplish the overall goal of mindfulness in the first place. As I said, mindfulness is about becoming aware of things as they are. From a Buddhist lens, becoming aware of things as they are really consists of two major things that we're trying to teach.

One is impermanence—that all things are impermanent. The second is that all things are interdependent or connected.

Impermanence starts to make more sense as we get older. It's kind of difficult for a child, but the way we talk about it is this: if we're outdoors, we can sit for a minute and do meditation just laying down and looking up at the clouds. We'll talk about how if you look at the clouds long enough, they come and they go. The clouds you were seeing five minutes ago aren't the same clouds you're seeing now.

I usually try to compare that to life itself. I explain to my kids that life is like clouds. Whatever life has in front of you right now—like looking up at the sky—whatever you see, that's what it is right now. But that's not what it will be, and that's not what it was, because it's always changing.

How well do they really get that? I don't know. That's why I don't dig too deeply right now into the concept of impermanence—I think that's a little harder to grasp. But there's another aspect of impermanence that I do discuss with my kids, and I think this is an easy way to convey the idea that life is constantly changing, that things that are at one point are no longer.

And that's using a bell. I have two meditation bells in my house. One of them is a little bowl with a wooden mallet that you use to hit it. What I like to do—I do this when I teach meditation to adults as well—is you can take a bell and this works with any kind of bell. You ring the bell and ask the kids to listen to it and raise their hand when they hear that it stops ringing. As soon as they raise their hand, they can open their eyes.

This works really well when you have several people in the room, because what they'll discover is that as they're listening intently to hear when the bell stops ringing, and they think it's stopped and raise their hand and open their eyes, often they'll notice that somebody else hasn't raised their hand yet. It doesn't usually happen at the exact same time. One hand goes up, and then maybe one or two seconds later, another hand goes up.

I like to explain to them that the nature of impermanence is that everything that has a beginning—or what we would typically think has a beginning or an end—when you listen to the bell, what you discover is that what you may have thought was the beginning or end of the sound may just be the end of the sound for you. But it's not necessarily the end of the sound for someone else yet. If you really pay attention to this and listen to the sound of a bell, it's very difficult to pinpoint exactly when it stopped. You can pinpoint when it stopped for you, but you can't really pinpoint exactly when it actually stopped, because it's different for every person.

So the ringing of the bell is another fun way to bring up the topic of impermanence. The clouds are another one I mentioned before. Those are two good ones for kids.

3. Teaching Interdependence: Everything is Connected

But the one that I've really focused more time on is the idea of interdependence. I think this is something that resonates well with kids, and it makes sense. The way we talk about this, I don't use the word "interdependence." The word I use with my kids is this: I tell them, "Did you know that everything is connected?"

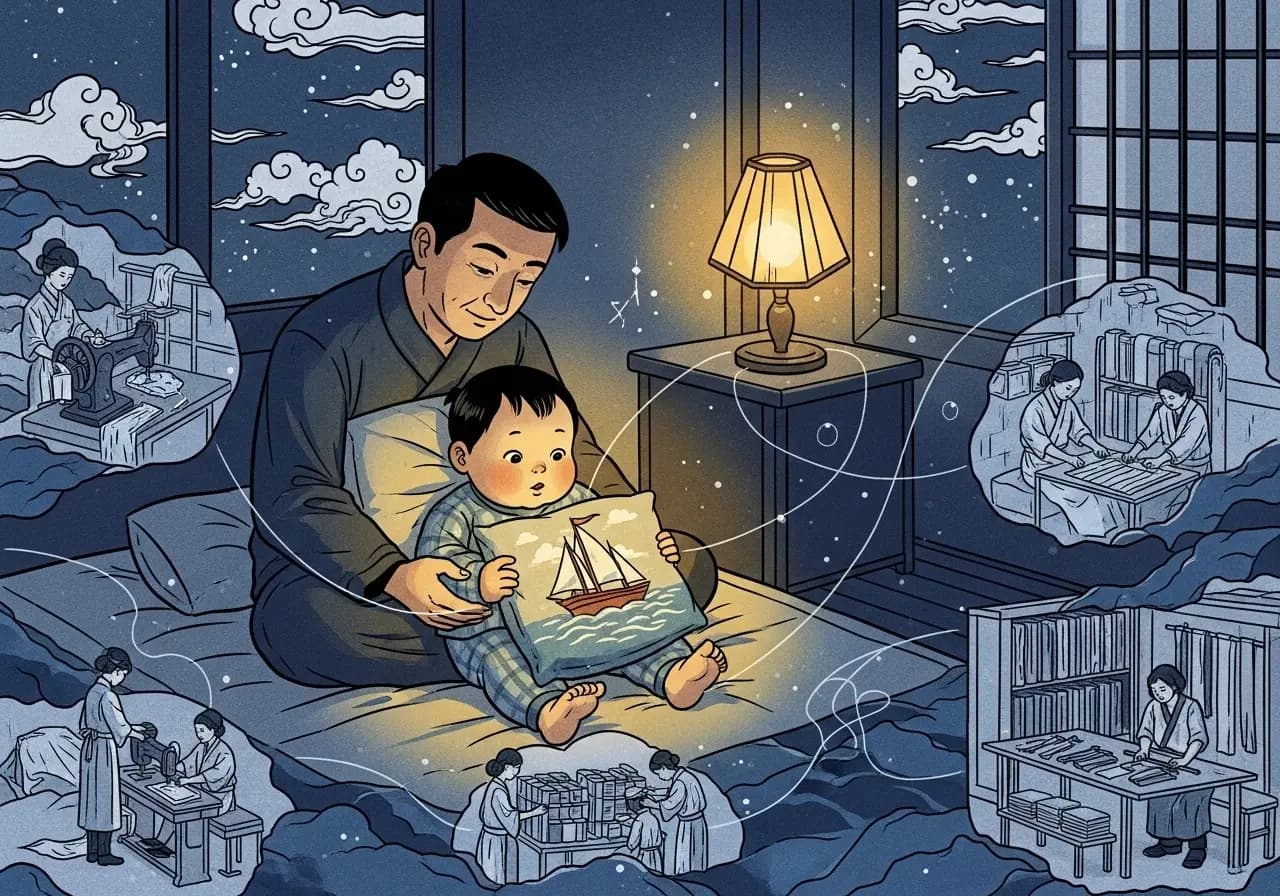

The way I convey this, I usually start when we're sitting in bed, either right before or right after meditating. Usually before, because sometimes my daughter's asleep after. We'll be sitting there and I'll say, "Riko, grab your pillow," or "Grab a stuffed animal," or just "Pick something in your room." He'll grab it.

I remember one time it was his favorite pillow. He's holding his pillow and I said, "So I want you to learn and discover that everything that you have connects you to someone." He said, "Well, what do you mean? Nobody else has owned this pillow. This is just my pillow."

I said, "I know, but let's look at the pillow." His pillow has fabric that's stitched, and it has a little print on top—like a sailboat print. I said, "Riko, I want you to look at your pillow and look at that print. Is that different fabric than the fabric of the pillow?" He said, "Yeah, that's not the same."

I said, "So I want you to imagine: did your pillow grow on a tree, or where did your pillow come from?" He thought about it for a second. And I think it's really important to allow them to make these connections on their own rather than telling them the answers. He thought about it and said, "Oh, somebody made it." I said, "Yeah, somebody somewhere made this." I said, "So you're connected to whoever made it, right?"

He said, "Oh yeah, okay. So that's what it means that everything's connected?" I said, "Yeah, but let's explore this a little more."

I said, "Whoever made it had to stitch it." We have a sewing machine at home and his mom does a lot of sewing. I said, "Mommy stitches stuff and makes dance costumes. Do you think somebody used a sewing machine like mommy has to make this pillow?" He said, "Yeah, they stitched the pillow. I can see all the stitching."

I said, "Yeah, well where do you think that person got the sewing machine?" He said, "Maybe they bought it at the store?" I said, "Yeah, so they must have bought it from someone, right?" He said, "Yeah."

I said, "Well now you're connected to the person who made the pillow and to the person who sold the sewing machine to the person who made the pillow." He said, "Oh wow, so it's two people?"

I said, "Let's keep going with that. The sewing machine—did that grow on a tree? Do sewing machines grow on trees, or are they just out in the forest? How do we get sewing machines?"

Again, he thought about it for a second and realized, "No, somebody made the sewing machine." And the process continues, right? I keep breaking it down. "Where did the string come from? The components of the sewing machine?" And what he kept discovering is that everything connects to someone else.

We talked about the person who drove the sewing machine once it was completed to the store. The person who invented the car. The person who invented tires so that cars can drive. And you can go on and on. This is a never-ending process. But you just pick the bigger, more obvious parts of the process that kids are gonna understand.

Suddenly, he just pauses and says, "Daddy, this pillow connects me to thousands and thousands of people." I said, "I know. Isn't that awesome? And we usually sit here and we look at this pillow and we think, 'It's just a pillow.' But it's not just a pillow. This little pillow connects you to so many people in so many countries and so many processes. All of these things happened so that you could just have this pillow right here on your bed."

Then he picks up his pillow and just hugs it and says, "Oh, I love this pillow."

It was just this moment of excitement for me because that's what you're trying to teach with interdependence—this understanding that we truly are interdependent and connected with everything. Something as simple as a pillow, something you may never think of, all of a sudden he saw it differently. And I don't think he'll ever see that pillow the same way again. That was a neat experience for me.

We continue that process. Everything is connected. I'll say, "Riko, now grab your little toy." We start the same process. He has a little dinosaur. He's way into dinosaurs. He's studying this dinosaur, breaking it down. He's like, "Well, this has plastic, but it also has screws." I said, "Yeah, do you think somebody put those on there? Maybe using their hands?" He said, "Yeah, maybe." I said, "Well, sometimes it's machines that do it. What if a machine did it?" And without even thinking, he just said, "Well, but somebody made the machine." I was like, "Exactly."

So then we were able to kind of explore the process of one of his toys for a little bit. I like to do this every now and then. I'll just pick something random and say, "Riko, what does this connect you to?" Then he'll study it and think about it. And I've been very impressed with how much more in-depth his understanding is with interdependence.

Without ever even using the word "interdependence," now he looks at things and studies them. Sometimes he needs to be prompted by me to get him thinking, but he can see things differently. He's learning to start seeing things as being connected. That's the whole point. That's the object of mindfulness—that we can start to learn to see everything as interdependent. And I'm starting to see that with my six-year-old.

With my daughter who's three, it's a little more difficult. But you can still kinda talk about it, and they get whatever they can get. As they get older, it makes more sense. So I think it's important not to get caught up in thinking, "How can I ensure that my three-year-old learns this?" or "My four-year-old learns this?" It may be that they don't until they're older. In my case, my six-year-old is really getting all of this. My three-year-old really isn't. And that's fine.

4. Sensory Awareness: Sight, Sound, Smell, and Touch

The third exercise that we've been doing is a component of mindfulness: becoming very aware of our senses, being aware of things as they are, just as we are. A good way to do this is to explore sensations through your physical senses—sight, sound, smell, and touch.

The way we do this, I'll kind of talk about each one separately. I don't do all of these at the same time at night. It's not like we go through all of these in one sitting. You do these throughout various times of the day. Usually at night, our routine is we talk about "Everything is connected. Pick something and let's see how we're connected to it." Once that discussion is over, we do meditation. That's really all we do at night.

But at other times during the day or at random times, I like to bring awareness to their physical sensations.

Sight

With sight, this is kind of a new thing I started, and I got this from my dad. My dad has, for years, had this habit: when he comes over, he'll take one of the little toys of the kids and just go hide it somewhere obvious. He'll take a little plastic figure and put it on one of the blinds, then see if anyone notices. And nobody notices. So after a while, he'll say, "Hey, have you seen that little Batman?" And then they're all like, "Huh," and they know the game has started. The kids know this. He does this with my kids and with my brother's kids, and it's a fun game. It becomes this moment of awareness: "Where is that little toy?" They know he hid it somewhere, so they start looking around, and they're like, "Where is it?"

And usually, they're looking around in places that they wouldn't think to look, and that's where they find it—like on top of the fridge or on the vase where the flowers are. It's usually somewhere hidden, but somewhere obvious. So I've started to try to do this a little bit with my kids. Sometimes when I'm playing with them, I'll take a little toy when they're not looking and hide it somewhere really obvious, right in front of them. Then I'll ask them, "Hey, where did that little Lego guy go?"

They know. As soon as I say that, they look around and they're excited to start looking. The object of this game is to start teaching them to look. That's really all it's about. What are they looking for? What do you see that's right in plain sight but you just don't see it? That's the object.

Usually, one of them will find it, and then we'll laugh and I'll say, "Isn't that funny how sometimes the things that we're looking for are right in front of us but we just don't see them because we don't typically look?" And that's about the extent of the lesson I'll give. Because again, I don't think they really grasp the deeper meaning yet. But it's an exercise and a routine that I plan on someday turning into a powerful lesson on insight and on mindfulness. For now, it's just a little fun game and an exercise that we do.

Smell

With smell, something you can do that's fun is maybe when they're sitting at the table or it's time to eat, you could pause and play a game where you say, "Okay, everybody close your eyes," and then you bring out what they're going to eat or maybe it's an orange or just a random object. You say, "You're not allowed to touch it, but you can put your head down and smell." Just see if they can smell it and, based on their sense of smell, decide what it is.

Again, it's really simple. It doesn't do much other than set you up at some point for teaching them that they can become aware of obvious sensations that are there that we don't usually pay attention to. At dinner, it can be as simple as, "Close your eyes. I want you to take some whiffs, smell, and see who can tell what we're having for dinner."

That exercise alone starts to train them to become more aware of what they are smelling. Again, it's one of the senses that's there, and unless you're paying attention and using it, you don't really do that in everyday life.

Sound

Sound—I mentioned the bell before, and that's a fun one to play with. Something I like to do: if we're just sitting there, and this one might be one I do at night, you sit there and just listen. You say, "Okay, we're gonna play a game. I want you to close your eyes, and I want you to listen. I want you to tell me: what do you hear?" You just sit there in complete silence. Maybe someone will say, "Oh, I just heard a car drive by."

Then you could develop that over time: "Well, do you think that was a car or was it a truck or was it a semi?" You want to refine their ability to sense what they're sensing—in this case, really hear what you're hearing.

We live close to a bigger road that's not that busy, but it's a state highway, so sometimes it's a truck, sometimes it's a tractor, sometimes it's a semi, and they can start to tell the difference between the sounds. But what you're trying to do is train them to become aware of what they are aware of.

Touch

Touch is another fun game. You can just sit down and say, "I'm gonna put something in your hands. Close your eyes. I want you to feel it and tell me what it is." This can be something as obvious as a stuffed animal. My kids love stuffed animals—they have like fifty of them. I'll take one and say, "Okay, I'm gonna put this in your hands. You're not allowed to open your eyes, but just feel it and tell me: which one is this?" They'll feel it and say, "Oh, this is the rabbit. Oh, this is the puppy."

But again, what you're doing is training them to become aware of the senses, to become aware of awareness. That's the whole purpose of meditation or mindfulness. Using sensations is a good way, a fun way, an easy way, and there's not really a deep lesson—at least not yet. You don't have to sit there and say, "Let me tell you what you're learning here." You just play, and you're increasing their ability to use their senses. That's kind of the whole point.

At some point, it becomes a very powerful lesson when they're older and they understand. Then you can explain mindful living as being very aware of everything just as it is. And that includes seeing things as they are, smelling as it is, hearing things as they are. You can kind of incorporate all that at some point. That's my plan, at least.

Bringing It All Together

So those are the four main ways that I try to teach mindfulness to my kids: the sound of a bell and clouds in the sky to discuss the concept of impermanence; playing the game of "Everything's connected—how are you connected to this?" to discuss interdependence; and using sensory awareness to explore their physical senses.

You can do this at dinner too. If you're gonna have a meal, it's fun to sit down and say, "Okay, where did this corn come from?" Then you talk about that for a little bit. "Where does corn come from? How do we get corn from the field to our table?" And discuss the whole process—from transportation to the machines that husk corn, just whatever you need to. And you can do this with any kind of food.

But it's a moment to become very mindful about what you're about to eat and where it comes from and how it connects you to everyone and everything that made that process available for you to just sit there and eat corn.

Interdependence, I've found, is perhaps one of the most powerful ways of being mindful—when we become mindful of how everything is so interdependent. The causes and conditions, the processes that are required for us to just do what we're doing. Whether that's eating, watching TV, playing with a toy—so much had to happen for this toy to be here. So much had to happen for this pillow to be here that I get to lay on. So much had to happen for this meal I'm about to eat.

These are things you can discuss constantly with your kids. This trains them to become very mindful of interdependence.

Closing Thoughts

So yeah, those are the four things: meditation, teaching impermanence through bells and clouds, teaching interdependence through exploring connections, and sensory awareness. I'd love to hear from you in the comments on the blog or on the website, on Facebook, or wherever you're seeing this. If you're listening to the podcast, maybe you can email me: [email protected].

I'd love to hear what works for you. How do you teach mindfulness to your kids? Hopefully, these tips and hints work for you as well as they're working for me. I've found it to be very rewarding and very enjoyable to see this process unfolding with my own kids and to see them becoming more mindful of life in general. It's really a neat process.

And I think it helps foster in them a sense of gratitude for everything, because they realize that for everything to be happening the way it's happening, a lot had to go into that. And that's what mindfulness really teaches.

Hopefully, these tips are good. Thank you for listening, and I look forward to talking to you guys again next time. Thanks.

For more about the Secular Buddhism podcast and Noah Rasheta's work, visit SecularBuddhism.com